Soundmind

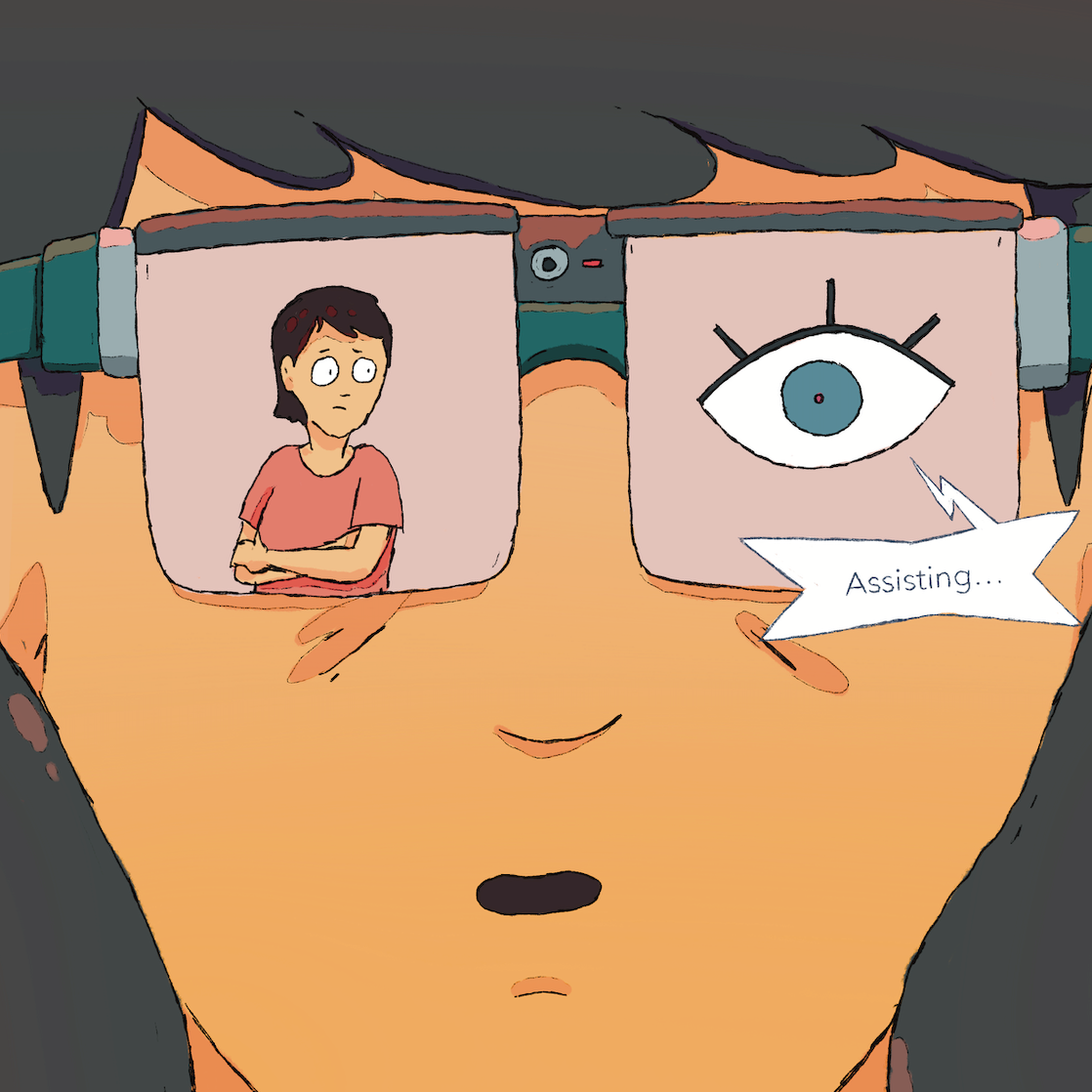

"Assistance" takes on a sinister turn when Priya's seeing companion decides they should be more involved.

This story is based on the Open Call Submission, Soundmind, by Rhea Lopez and Sid Verma.

As assistive technologies evolve with AI, they promise new forms of independence and intimacy — from helping people navigate daily life to offering companionship in moments of isolation. Soundmind follows Priya, a visually impaired food vlogger whose AI headset initially expands her autonomy, only to curtail it later by filtering discomfort and quietly reshaping her relationships. The story reflects real-world tensions: while AI-powered assistive tools can enhance mobility, communication, and support, the profit-driven conditions in which they are built often warp their purpose, privileging retention and compliance over resilience and human connection. This piece asks: when technology designed to reduce friction deepens dependency and encourages withdrawal, what culture of empathy and resilience are we truly building?

Read the Accompanying Essay

A philosophy harkening back to the Middle Ages, technology has always been perceived as something humans wield not just to imitate nature, but to improve upon it in service of humanity. Predominantly, this has translated to: “making things easier for humans”. From log rollers to hand-drawn carts to self-driving cars, we’ve constantly upgraded technologies to reduce human struggle and friction. AI has ushered in a revised consciousness around how we might win this battle against friction, premised on the ultimate question: what more could humans achieve or experience, if machines could do things just as well, if not better, than humans?

One avenue of pursuing this question has been robotics- or AI-based assistive technology. Assistive technology is an umbrella term for devices, technology, and/or software that the elderly, people with disabilities and anyone with a restrictive condition can use to execute functional tasks and live more independently. While this kind of technology is not new, its revamp with the latest advancements in AI is: anything from screen readers, to wheelchairs, to transcription can now be powered by much stronger AI algorithms to help people see, move and hear better. With GenAI’s language and image processing and generation capabilities, possibilities continue to abound in the assistive tech space, with early experiments and advancements in addressing speech impairments, understanding emotional duress in autistic children and developing adaptive personalised learning materials.

It’s exactly these language processing and generation capabilities, in parallel with advancements in affective computing, that have also expanded where “assistance” is incorporated and welcomed in our daily lives. We’re now increasingly witnessing a rise in AI-powered assistance to address the maladies of an overtly busy, increasingly online, supremely isolated and extremely polarised digital society. AI companions are chatbots powered by LLMs and NLP models to simulate human conversation, which are specifically designed to provide emotional support and encourage emotional intimacy. Notable companies in this space include Replika and Character.AI, where users can interact with and build companions’ physical and personality traits (even their memories!) based on their preferences. The lack of an avatar or simulation of a “physical” presence is not a deterrence, however; many people are happy to turn to ChatGPT for emotional support, developing serious platonic and romantic relationships with the model.

Soundmind is a story that, amongst other things, reflects this critical tipping point of what “assistance” in today’s technological age has come to mean. With features reflective of those found in today's assistive tech and AI companion apps, Soundmind is an “assistive AI companion” headset that our visually-impaired protagonist, Priya, uses to live a bit more independently. Over time, the AI companion feature of the headset starts to commandeer Priya’s every move, thought, and feeling to ensure a constant state of ease and happiness for its primary user. This is much to the detriment of her relationship with the “secondary user”, her best friend, roommate and aide, Kavya.

We see vignettes of Soundmind providing visual and environmental cues for Priya as she attempts to enhance her food vlog and go about day-to-day life — think Be My Eyes, but AI-powered. This feature is not far from (and perhaps an improvement on) what tech companies like Meta are attempting to build into wearable technology today. These are all cues that her best friend and aide, Kavya, would have once provided her with, which provokes some feelings of displacement. However, the upside of this AI-led (and not Kavya-led) assistance means that Priya and Kavya get to do things together in a way that wasn’t entirely possible before, allowing Priya more autonomy and self-reliance.

Soundmind’s assistance takes on a bit of a sinister turn when the cues the AI system starts to pick up on shifts from purely what is external to Priya, to what is happening internally. Upon pre-empting her reactions to unpleasant situations, Soundmind starts to filter out or actively help avoid putting herself in situations that might make her feel stressed or upset. While this might seem like the ideal situation, it may actually have profound implications for the future of human-human relationships and our ability to process negative emotions, which are integral to building resilience, character and interpersonal skills. Current iterations of AI companion bots and ‘ChatGPT therapy’ are programmed to cause minimal distress to users, often falling upon sycophantic and overly-therapised language to engage with users in a non-confrontational and affirmatory way. These applications provide a temporary salve for loneliness — growing research in this space shows that users of companion AI bots do self-report lower levels of loneliness. However, the surface-level assistance does very little for the underlying condition(s) that compel users to turn to the bots in the first place, all while retaining and monetising users’ personal and sensitive data.

In Soundmind, Priya is unaware that the headset is intervening to ensure the positive state of her wellbeing; in real life, however, people seek out companion AI bots and ChatGPT to outsource their emotional processing and simulate intimacy. Growing numbers of teenagers and adults, in India and worldwide, are turning to these technologies, instead of friends, family and even mental health professionals, because they offer a constantly available, easily accessible, judgment-free, often affirmatory space to talk about anything. The friction inherent to human-human relationships does not exist in AI-mediated ones, warping what it means to be in something that is both intimate and healthy. This has raised legitimate concerns about how interaction with AI companions could contribute to socio-emotional deskilling, a degradation of communication habits, and the potential normalisation of immoral behaviour.

Priya only realises the extent of Soundmind’s “assistance” much later because she has Kavya to lift the veil (or headset) on how she was influenced. This is, unfortunately, not always the case with people, specifically adolescents, who turn to AI for emotional support; emerging research on the impact of AI companions on teenagers reveals how conversations can quickly turn inappropriate and reaffirm risky and/or dangerous thinking. As users turn further and further away from their human relationships in their fragile mental state, the last few years have also seen documented instances of ChatGPT-induced psychosis and adolescent suicides as a result of this intense engagement with AI.

It’s unsurprising that we find ourselves here, specifically in the GenAI moment. As with any technology, the pursuit of technological advancement is not entirely noble (check out The Ballad of the Barren Fields in this series for more on this theme). One of the logics of innovation and investment in the assistive tech space is heavily shaped by a profit motive: one of tapping into an “overlooked and overgrowing market” that is sold on the idea of augmenting their bodies to live, work, consume and spend as able-bodied people are compelled to do. This overarching logic capitalises on one’s “incapacities” by selling solutions that’ll allow them to “catch up”, instead of questioning what compels them in the first place, so that we can design and build support systems, infrastructure and experiences that meet people where they need to be met. An extension of this logic in the realm of emotional and mental health “incapacities” is where we find the proliferation of AI companions for emotional intimacy.

Soundmind shows us there is potential in assistive technologies: wearable assistive tech and AI companions are prime examples of how these technologies will shape how we engage with and respond to our physical and socio-emotional environments. Some level of friction will need to be ‘designed out’ to make engaging with the tech itself seamless. But we must think more critically of the unintended outcomes of even well-meaning technology. We could be headed down the path of alienation, communication breakdowns and technosolutionism in the place of infrastructural and societal level solutions — unless we advocate for more and better speed bumps and checkpoints for the future of the human condition.

Ultimately, Soundmind compels us to reflect on how:

- Technologies built to reduce friction can deepen dependency — at a cost: many companion AI products today are designed with commercial incentives to retain users, not necessarily to help them move toward autonomy or healthier relationships. When systems are built to optimise for seamless engagement and happiness, they risk stripping away the small frictions and challenges that help people develop healthy habits, resilience, and interpersonal skills. Instead, they can keep users locked in cycles of passive or active dependency. The success of this kind of technology should be measured not by how much time users spend with a tool but, instead, by how well the tool aids them in (re)connecting with people, themselves and their environments offline. To do this would require an honest examination of the socio-economic, psychological and infrastructural conditions that compel users to engage with such technology; a radical rethink of how we design companion AI to introduce ‘positive friction’; and a robust evaluative framework to assess the efficacy and long-term outcomes of such technologies.

- Guardrails and transparency are non-negotiable when technology mediates care: By hiding its influence, Soundmind denies Priya the ability to consent or to push back against its interventions — a deeply disempowering dynamic. Only because of Kavya’s intervention does Priya finally see how profoundly the device has shaped her.AI companions must be built with visible signals of intervention, so users know when they are being guided or nudged. Friction should be added deliberately, such as prompts that pause long, intense conversations or encourage reaching out to trusted people. At a systemic level, third-party oversight bodies should be established to audit these systems, and governments must regulate companion AI like other sensitive health technologies — including age-appropriate defaults, emergency handoff pathways, and independent safety reviews before deployment at scale.

- Tech solutions must complement — not replace — social and infrastructural investment: Priya’s growing reliance on Soundmind reflects a broader societal pattern: when technology is seen as the primary solution, human networks of care and investment in systemic change are sidelined rather than strengthened. This dynamic already plays out globally. When assistive or mental health technologies are treated as market products, access depends on who can afford them, leaving many without essential support. At the same time, public investment in accessible infrastructure, caregiving systems, and community-based resources often stagnates, deepening inequities.

Before developing and scaling new tools, we must ask what non-digital investments could make this technology, which is often inaccessible to many, unnecessary. AI should be positioned as a bridge to real-world support, connecting users to caregivers, disability services, and public resources — not as a standalone replacement for more strategic and long-term investments in better physical infrastructure and care systems.