The Wandering Healer

A community health worker finds that a new Generative AI tool increases her workload and strains patient relationships, so she repurposes a discarded medical robot to offer a more human-centered, AI-enabled alternative.

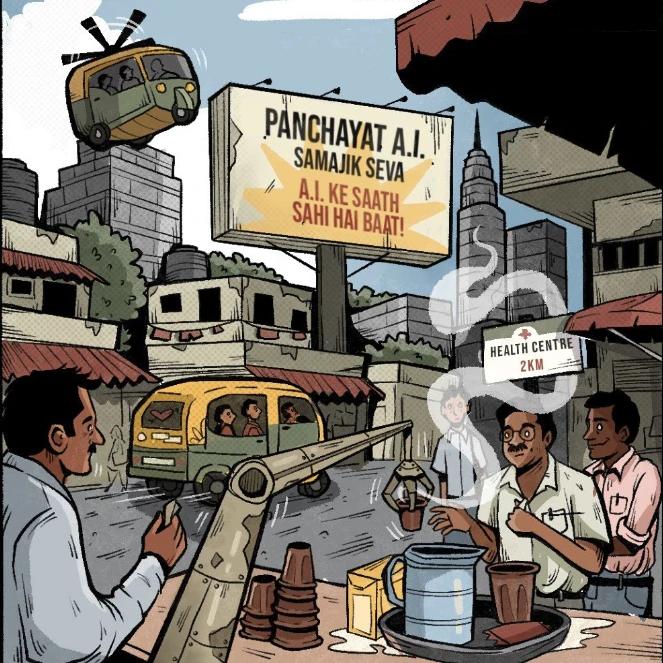

As GenAI tools enter healthcare, promising increased efficiency, their impact on India's frontline ASHA workers reveals deeper tensions. While AI tools can help health workers serve more patients faster, they also pressure them into higher quotas, undermine patient relationships, and reinforce systemic inequities, such as chronic underpayment and surveillance. Instead of empowering ASHA workers, efficiency-driven AI risks reducing care to a checklist, sidelining the vital human elements of trust, empathy, and context.

But a different path is possible. The Wandering Healer imagines a future where technology is designed around an ethic of care — valuing ASHA workers' invisible labour, supporting holistic patient care, and challenging entrenched power structures.

This piece asks: Who should AI serve, and what kind of healthcare future do we want to build with GenAI?

Read the Accompanying Essay

Across various sectors, GenAI tools and applications are being introduced to boost worker productivity. In the healthcare space, emergent GenAI applications can support doctors and nurses with tasks ranging from report summarisation to medical diagnoses and data entry.

Applications that support Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA workers) in patient care are also in development. ASHA workers are community healthcare workers who form the backbone of India’s healthcare system. Trained to act as health educators and health promoters in their community, ASHA workers help marginalised communities access healthcare at their doorstep. However, numerous reports highlight how ASHA workers are overburdened. When the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare first recruited them, ASHA workers were expected solely to document births in their neighbourhood. Their work has now expanded to cover all aspects of a community’s healthcare needs.

New GenAI applications aim to support ASHA workers by providing quick and easy access to relevant medical information in multi-modal formats and various languages. The timely access to information is expected to improve their responsiveness to health queries from the communities in which they work. It can also help them save time as they no longer need to rely on their supervisors to access relevant medical information.

GenAI tools can potentially help ASHA workers support patients more effectively, facilitating streamlined patient interactions and more exhaustive coverage while also helping them adhere to prescribed health guidelines.

In ‘The Wandering Healer,’ we see Nandini, a community-based healthcare worker, assisting more patients than usual due to the introduction of the new GenAI Sahara Superband 2.0. As an efficiency-enhancing tool, it enables her to cover more patients in the same amount of time.

However, these initial gains in worker productivity from AI tools can quickly turn into pressure on healthcare workers to meet ever-increasing targets. What starts as a promise of efficiency becomes a source of stress, as supervisors push for higher daily quotas. However, the focus on speed in healthcare delivery often comes at the cost of quality of care. As we see in the story, Nandini finds herself unable to devote enough time to each patient; her interactions are constantly interrupted by AI-generated reminders urging her to move on to the next patient.

These tools may thus also reshape interactions between healthcare workers and patients. Patients who once saw health workers as empathetic guides may experience a more transactional form of care, where checklists and automated recommendations take precedence over human intuition, context and care. We see this come to a head in Nandini’s interaction with Rekha, a woman still hoping and trying to get pregnant, who feels slighted by Nandini’s adherence to the Sahara Superband 2.0’s rigid schedule. The interpersonal, trust-based relationships that health workers have nurtured with their communities become secondary to fulfilling directives driven by AI. The result is a system that reduces patients to mere numbers, leaving both workers and patients shortchanged.

Moreover, the additional workload resulting from the use of AI, higher targets, and maintenance of logs, for instance, is often not accompanied by an increase in compensation for healthcare workers, reflecting a persistent issue in India’s public healthcare system. Community healthcare is often seen as ‘gendered community service’ or an extension of female caregiving and thus remains financially undercompensated. In most states, they do not receive a fixed pay despite working 8-12 hours a day.

The introduction of GenAI tools in community health can also quickly morph into a mechanism for worker surveillance and control, dictating how ASHA workers allocate their time and attention. In the story, Nandini is reprimanded by the Sahara Superband for spending a few minutes chatting with a friend between patients, and she is instructed to spend less time on interactions with patients that are not work-related. To stay efficient and productive, small and often necessary allowances for human connection and rest are gradually eroded.

At the same time, the deeper challenges faced by ASHA workers – such as inadequate compensation, lack of social protection, and chronic overwork – remain largely unaddressed, even with the introduction of GenAI tools.

While the technology may change the execution of tasks, it does little to alter the structural conditions that continue to undervalue and exhaust these frontline workers. This begs the question: Who does the GenAI tool serve? If it is meant to improve working conditions for ASHA workers, shouldn't we be listening to them to identify the issues that concern them the most? India’s public health system still struggles to reach the most marginalised, depending on underpaid ASHA workers to fill or work around systemic gaps in healthcare access. Why is our imagination of a tech-enabled health system limited only to efficiency-driven piecemeal solutions? Why can we not use technology to reconfigure the hard-coded inequities in our healthcare system?

In ‘The Wandering Healer,’ DOST represents a new logic for technological development. Rather than being optimised to improve system efficiency, it is optimised to enhance an ethic of care. This moment in the story reflects a subtle but crucial point: AI systems, like any other technology, are continually optimised for some goal or objective. And we, as a society, can exercise choice in deciding those goals.

An ethic of care mandates directing attention to vulnerability and dependency in the context of where and how they arise. It requires paying attention to the quality of human relationships and prioritising context-specific care over generalisable or uniform prescriptions. Originating from feminist principles, an ethic of care also seeks to expose and challenge existing power structures within systems.

Applied to the context of ASHA workers and healthcare delivery, building AI systems on an ethic of care means starting with listening to the needs of ASHA workers themselves. In the story, DOST captures the unpaid labour of the health workers in the village, whether in terms of something as basic as travelling time from one village to the next or something as nuanced as the quality of care and comfort they provide to their patients.

If AI could analyse the impact of ASHA workers’ holistic care efforts, including counselling, follow-ups, and emotional support, it could help establish new metrics for evaluating their contributions. It can assign value to this effort in a way that allows ASHA workers to secure genuine recognition for their work, specifically in the form of improved wages and working conditions.

Crucially, the essence of healthcare lies in care itself — something that AI tools optimised for efficiency may not always account for. The work of an ASHA worker is not just about recording symptoms and administering checklists; it also includes providing reassurance to anxious mothers, counselling families on nutrition, and offering support that is difficult to quantify. Community members would benefit from an approach that stems from a relational understanding of their position, rather than one that dismisses it as inconsequential to their health needs.

This shift is not merely hypothetical — it represents a broader reconsideration of what AI should optimise for in healthcare. Efficiency is undoubtedly important, but when it comes at the cost of genuine, context-specific care, the system risks losing its most vital human element. By designing AI tools optimised for an ethic of care, we can envision a future where ASHA workers are empowered rather than overburdened, where communities receive holistic, encompassing support rather than purely clinical prescription, and where technology serves as an enabler of care rather than an instrument for productivity.

The Wandering Healer is ultimately a reminder to:

- Listen and consult with the people technology intends to support. The technology aimed at addressing the concerns and challenges of ASHA workers may be far removed from their actual needs, such as adequate compensation and improved working conditions. Without efforts to engage with them, top-down technology design and development processes are likely to be ineffective and may even contribute to new harms and risks.

- Consider the logic or goals AI optimises for — efficiency is not always the most important or beneficial goal. In healthcare, contextualised patient care and empathy are just as critical.

- Reimagine the opportunities AI can offer us; it doesn't have to be limited to piecemeal solutions. AI can also be harnessed to challenge existing power structures and shift persistent power imbalances. In the story, Nandini programmes DOST to optimise and capture metrics for care, which supports her and her peers in providing holistic care to their communities, while also quantifying the value of their work. It’s a (re)programming of AI that aims to bridge the gaps in the system, instead of working around them.